Sameer Farooq’s chic work The Flatbread Library, a spotlight of this yr’s Toronto Biennial of Artwork (till 1 December), was impressed by the artist’s 2019 go to to Pakistan together with his father.

Farooq—who grew up in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, the place his Pakistani father was a health care provider and Ugandan Ismaili mom a midwife—was staying within the mountainous area of Peshawar bordering Afghanistan together with his aunt. A visit to the native tandoor, a neighborhood bakery frequent in South Asia the place locals take their bread to be baked, proved revelatory.

“I used to be actually impressed sculpturally by all of the various kinds of bread there,” Farooq tells The Artwork Newspaper.“That they had completely different textures and stamps denoting particular bakeries and every bakery had its personal sample or motif printed on the bread.”

He explains that bakers will purchase bread stamps from woodworkers out there to place patterns on the bread and make different markings and indentations with their fingers to indicate a type of signature. Usually, they are going to place bread on carpets hanging from hooks, or they are going to lay it flat on rugs on the bottom as a type of show.

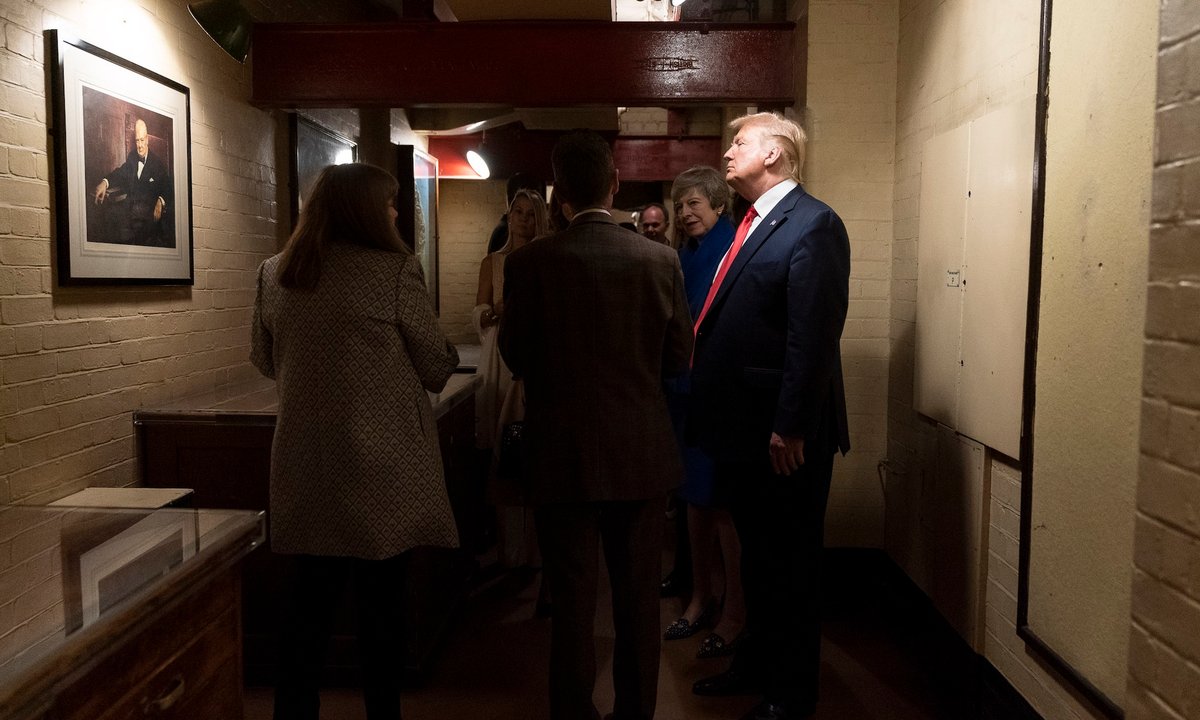

Sameer Farooq together with his set up, The Flatbread Library, as a part of the 2024 Toronto Biennial of Artwork © Hadani Ditmars

It was a eureka second for the Toronto-based artist, the place he reimagined flatbread as a type of textile, one he weaves collectively in his set up with grace and ingenuity. It was additionally the start of years of analysis into tandoors that took the artist to Turkey, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Morocco and Mexico. He found that in every single place, these ovens had been autos for constructing neighborhood.

“My dad at all times says that bread is just like the newspaper,” he says. “When the baker delivers bread door to door, she or he additionally spreads the information and the gossip of the neighborhood.”

He additionally discovered that flatbread enjoys a type of universality, transcending borders and identities just like the Sufi traveller of the meals world—one thing that Farooq recognized with personally. He sees flatbreads as repositories of “embedded reminiscence” each collective and historic.

Sameer Farooq, Flatbread Library, 2024. On view at The Auto BLDG, ninth Flooring as a part of the Toronto Biennial of Artwork, 2024. Co-commissioned and co-presented by the Toronto Biennial of Artwork and the Agnes Etherington Artwork Centre. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nicolas Robert. Pictures: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Knowledgeable by his observe of critically studying and reimagining museum narrative methods, the flatbread story quickly grew to become an obsession. In 2020, Farooq constructed a tandoor oven set up on the Scarborough Museum and, in February 2023, one other on the Materia Abiertaschool in Mexico Metropolis. In each instances, he held neighborhood gatherings across the ovens the place flatbread was baked and shared.

He additionally started to deal with the flatbread as an artwork materials, making ready a present at Le 19 CRAC, a cultural centre within the French Alpine city of Montbeliard close to the Swiss border within the winter of 2023. That was a “maquette” for his Toronto Biennial mission, he says.

With joint funding from the Toronto Biennial and the Agnes Etherington Artwork Centre at Queen’s College, the place he was an artist-in-residence earlier this yr, he started researching the various diasporic bakeries within the Better Toronto Space that used tandoors or different kinds of neighborhood ovens to make flatbread. These ranged from Armenian, Indian and Mexican to Afghan, Iranian, Pakistani, Lebanese and different flatbread traditions. He additionally met a Gazan mom and her daughter who had their very own conventional clay oven on their porch the place they made Palestinian taboon. Farooq ready a particular booklet that includes interviews with the ladies concerning the connection between their bread, their historical past and ancestral recollections of meals.

Sameer Farooq, Scraps (1–4), 2024. On view at The Auto BLDG, ninth Flooring as a part of the Toronto Biennial of Artwork, 2024. Co-commissioned and co-presented by the Toronto Biennial of Artwork and the Agnes Etherington Artwork Centre. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nicolas Robert. Pictures: Toni Hafkenscheid.

All of those breads are described intimately in a particular publication accompanying his Toronto Biennial exhibition, describing the fragile lavash from Iran, Armenia and Turkey, the Indian naan and roti, and the Mexican tortilla—every with its personal distinctive design, texture and flavour.

Drawing on his background as a ceramicist, Farooq makes use of a way employed in making clay tiles. He dries the breads underneath drywall boards, the plaster within the drywall pulling the moisture out of the breads whereas conserving them flat. As soon as the breads are dry, he coats them with shellac and a product referred to as “flexi paint” that nearly rubberises the breads, making them much less fragile and simpler to work with.

Using the breads as sculptural supplies and impressed by the “curtains” of sangak seen within the markets of Iran, he hangs them from a easy wood body, backed by netting and carpet, suggesting a flowing textile. The impact is a type of flatbread sanctuary, the place completely different nationalities of bread—and, by extension, completely different peoples—coexist and join, their histories interweaving.

“The phrase for bread in Egypt is aish or ‘life’,” he says. Contemplating bread’s borderline sacrosanct standing, it’s thought-about a sin to throw it out, so Farooq used scraps of leftover bread to supply a collection of monoprints, coating them with oil-based ink then putting them on paper. The bread compositions had been then handed via a printing press and the bread was eliminated, revealing the print. The fragile, ephemeral patterns resemble fingerprints or stamps—and echo the biennial’s title, Precarious Joys.

Sameer Farooq, Flatbread Library, 2024. On view at The Auto BLDG, ninth Flooring as a part of the Toronto Biennial of Artwork, 2024. Co-commissioned and co-presented by the Toronto Biennial of Artwork and the Agnes Etherington Artwork Centre. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nicolas Robert. Pictures: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Farooq additionally made sculptures of preserved bread: two pagoda-like stacks of round breads and and considered one of rectangular formed ones he calls a “library”.

Whereas the works themselves are libraries of embedded, imprinted reminiscence, the big hanging set up can be a type of various map of Toronto: a metropolis of diasporic neighbourhoods expressed via the sweetness, the fragility and the very ephemeral nature of the stuff of life.

On 3 November, Farooq has invited all the native bakers he befriended to return to a feast of flatbreads, extending a banquet desk out from the set up and providing up a scrumptious sense of neighborhood.

Sameer Farooq: The Flatbread Library, till 1 December, The Auto BLDG, ninth ground, Toronto, a part of the 2024 Toronto Biennial of Artwork