Among the many most intriguing objects within the British Museum is the Asante Ewer, a bronze jug made in England for Richard II within the 1390s, which in some way ended up in West Africa. In January 1896 the ewer was looted by UK troops from the Asante (Ashanti) king, in what’s now Ghana, and returned to London. Six months later it was offered to the museum. So, what’s the object’s present moral standing? Might it presumably have been looted twice?

The thriller is how the ewer reached the Asante capital, Kumasi, which is round 5,000 miles away. There have been two attainable routes. It might have travelled on an English ship to North Africa, from the place it might have been despatched overland by camel, throughout the Sahara to Timbuktu after which on to Kumasi. Alternatively, it could have passed by sea, presumably as early because the 1470s on one of many first Portuguese voyages round West Africa.

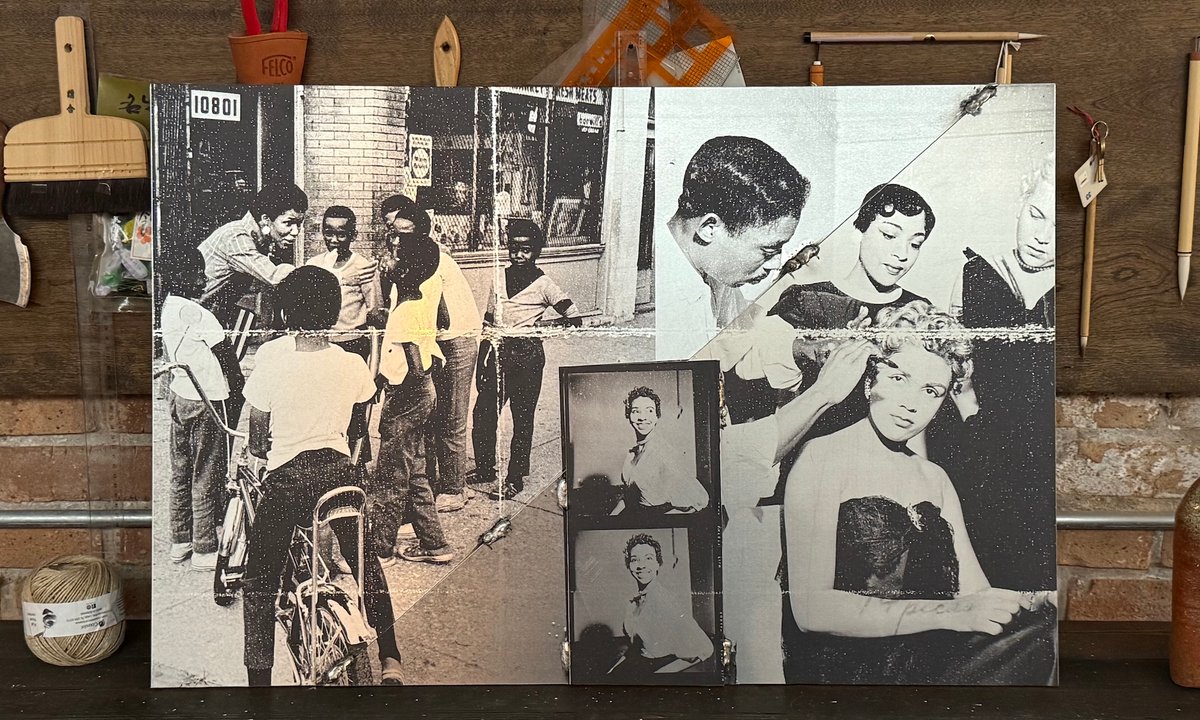

The Asante Ewer has a lid adorned with stags, sides engraved with eagles, and the entrance with the royal arms of England© The Trustees of the British Museum

The British Museum is now investigating the story of the Asante Ewer, as a part of a undertaking to look at early connections between England and West Africa. Lately this relationship has been studied primarily when it comes to the slave commerce, however the museum additionally needs to delve deeper into earlier hyperlinks.

The undertaking, funded by the British Academy/Wolfson Basis, is predicted to result in an exhibition or show centred across the Asante Ewer, to be held on the British Museum and Leeds Metropolis Museum (which has a smaller ewer, additionally looted from Kumasi). It will in all probability be held in 2025-26, when the British Museum curator Lloyd de Beer is publishing a scholarly e-book.

Extremely valued

The imposing lidded Asante Ewer, 62cm tall and weighing 22kg, is way too heavy to have ever been used for pouring liquids; it was in all probability a status object made for show. Casting such a big bronze ewer would have required nice ability.

The ewer is ornately adorned. Beneath the spout are the royal arms of England, as used from 1340 to 1405. However the ewer might be dated extra exactly, for the reason that stag decorations on its seven-sided lid characterize the non-public emblem of Richard II, suggesting that it was solid throughout his reign within the 1390s. A 3-line inscription in aid lettering (translated into trendy English) ends: “Deem the most effective in each doubt till the reality be tried out.”

This 1884 {photograph} of the royal compound in Kumasi in modern-day Ghana exhibits the Asante Ewer and a smaller vessel, which is now at Leeds Metropolis MuseumInternational and Commonwealth Workplace Library

An 1884 {photograph}, taken over a decade earlier than the looting, exhibits the Asante Ewer and the smaller vessel (now in Leeds) below what was in all probability a sacred tree within the courtyard of the royal compound in Kumasi. The presence of the 2 prominently displayed English ewers means that they have been then extremely valued by the Asante rulers.

The Asante Ewer was seized when British troops ransacked the Asante king’s compound in Kumasi throughout the Anglo-Ashanti Wars in January 1896. It was acquired by a senior officer, Charles St Leger Barter, who offered it to the British Museum for £50.

“I used to be lucky sufficient to safe it from the officer to whom it fell”

Charles Learn, then the museum’s keeper of British antiquities, described the ewer (within the language of the time) as “among the many paraphernalia of a negro king”. He added: “I used to be lucky sufficient to safe it from the officer to whom it fell. He had the perspicacity to choose the ‘outdated jug’ to the extraordinary savage weapons and blood-stained sacrificial stools”.

Together with the Asante Ewer, two different smaller and easier jugs have been additionally looted by the British at Kumasi. These two are related to one another, suggesting that they have been solid in the identical foundry. Since all three ewers ended up in West Africa, it’s doubtless (however not sure) that each one got here from England’s royal family. A technical examination of the three, together with their steel composition, is now deliberate.

“It was the good battle fetish of the Ashanti Nation, all the time taken into battle”

The smaller ewer that seems within the 1884 {photograph} was acquired by the governor of the Gold Coast (because the territory was then recognized) throughout the 1896 navy operation and was instantly offered to West Yorkshire Regiment officers. It later handed to York Military Museum and is on long-term mortgage to Leeds Metropolis Museum.

The third ewer was acquired by the British Museum in 1933 from Cecil Hamilton Armitage, who fought within the Anglo-Ashanti wars of 1896 and 1900. A museum publication on the time of the acquisiton data that it was “the good battle fetish of the Ashanti Nation, and was all the time taken into battle”.

Mysterious voyage

Though the ewers could have been offered or stolen from England’s royal family, they’re extra prone to have been dispatched as diplomatic presents. They in all probability left London within the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries.

The puzzle stays: how did the ewers attain Kumasi? If diplomatic presents, there would have been little motive for English kings to have wooed the Asante at this early stage, earlier than it grew to become an amazing kingdom. However the ewers might have been a present to a North African ruler, whose successors subsequently despatched them throughout the Sahara.

Alternatively, the ewers may need been acquired by merchants and brought to West Africa by sea. Portuguese ships started to discover the Ghanaian coast from the 1470s. It’s simply attainable that they first reached Lisbon by means of Philippa of Lancaster, who was born into the English royal household and have become queen of Portugal in 1387.

If the ewers had remained within the UK a few years later, then English vessels started arriving in West Africa from the 1540s. The big-scale commerce in enslaved folks by means of Ghanaian ports solely started within the 1600s and the ewers in all probability arrived nicely earlier than then.

Bought or stolen?

The current moral standing of the ewers is advanced. Though looted by the British in 1896-1900, they got here from England. It stays unclear whether or not they left the family of Richard II in correct circumstances or have been stolen. Nevertheless, as soon as they reached West Africa, it is rather doubtless that they got (or presumably offered) to a strong determine in what’s now Ghana, as a official acquisition. Because the Asante kingdom was solely shaped within the early 18th century, the ewers would possibly nicely have been delivered to Kumasi from one other West African group, presumably because the spoils of battle.

The Asante Ewer is at current displayed within the British Museum’s medieval gallery, though the smaller ewer just isn’t on present. The 2 have been collectively in 2020-21 within the exhibition Caravans of Gold: Fragments in Time: Artwork, Tradition, and Trans-Saharan Commerce, offered in Washington, DC; Toronto; and Evanston, Illinois. The Yorkshire ewer is at current on show in Edinburgh, within the Nationwide Military Museum’s exhibition Legacies of Empire (till 21 January 2024).

The 2025-26 London and Leeds show would be the first alternative to see all three vessels collectively. Hopefully, De Beer’s analysis will get nearer to fixing the thriller of how these 700-year-old ewers reached West Africa.